Published in Nacional number 607, 2007-07-03

INTERVIEW

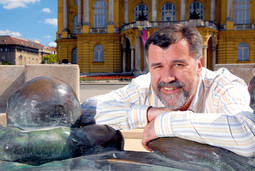

Veran Matic – Civil Serbia’s media magnate

DIRECTOR, EDITOR AND CO-OWNER of Belgrade’s B92 spoke to Nacional about how his media house expanded from a radio station to the Internet and television, and how he survived persecution under Milosevic’s rule

DIRECTOR, EDITOR AND CO-OWNER of Belgrade’s B92 spoke to Nacional about how his media house expanded from a radio station to the Internet and television, and how he survived persecution under Milosevic’s rule Veran Matic, director and chief editor of B92, the leading independent media house in Serbia, was celebrated in the 1990’s for being a great antagonist to the regime of Slobodan Milosevic; today, he is a successful and modern businessman and the director of a growing media house. What began in 1989 as a local radio station in Belgrade, currently covers the entire core of Serbia and Vojvodina. In the meantime, the B92 media house has expanded into a television station, with the third highest ratings in Serbia after state owned RTS and Pink, as well as an Internet portal which is the most visited in the Balkans, with approximately 100,000 individual users each day. B92 operations also include a publishing house, Internet provider and cultural centre. As an independent media under Milosevic, B92 and its boss experienced many inconveniences; Matic’s life was even in danger in 1999, when there was a plan to murder him after the assassination of Dnevni Telegraf (Daily Telegraph) publisher Slavko Curuvija. At that time B92 was banned, and Matic was arrested and detained for a short period. After Milosevic left politics, Matic and other leading people within B92 managed to maintain an independent editorial policy by not allowing the entrance of dirty capital into the ownership structure; recapitalization was done through investment funds, while a significant part of the shares were held by Trast B92, a company where B92 editors and managers have management rights, but cannot sell their stakes to anyone. Last week in Zagreb, Matic participated in the South East Europe Media Organization (SEEMO) conference, co-organized by the NCL Media Grupa. The topic at the SEEMO conference was “European standards and practice in Serbia” and there was a warning that the implementation of these standards were postponed due to fear that there would be a loss of the control mechanism over the media which was created in the former period, as well as the fact that the pluralism of solutions in European countries is being used in order to show everything as being a European standard. “At the 618th annual celebration of the Kosovo battle, I played around with the motives and facts that Milos Obilic is considered by Serbian media-mythological interpretation to be a Serbian, while Albanians call him Kobilic and refer to him as their own; when Serbia and Albania were in a alliance, he stabbed one of the then world leaders, the Sultan Murad IV and I asked whether this classified as a war criminal and if it would be necessary for my colleague the Albanian from Kosovo and I to apologize to Turkey for this crime, and, based on the current standards, should Obilic/Kobilic be put to trial“, said Matic.

DIRECTOR, EDITOR AND CO-OWNER of Belgrade’s B92 spoke to Nacional about how his media house expanded from a radio station to the Internet and television, and how he survived persecution under Milosevic’s rule Veran Matic, director and chief editor of B92, the leading independent media house in Serbia, was celebrated in the 1990’s for being a great antagonist to the regime of Slobodan Milosevic; today, he is a successful and modern businessman and the director of a growing media house. What began in 1989 as a local radio station in Belgrade, currently covers the entire core of Serbia and Vojvodina. In the meantime, the B92 media house has expanded into a television station, with the third highest ratings in Serbia after state owned RTS and Pink, as well as an Internet portal which is the most visited in the Balkans, with approximately 100,000 individual users each day. B92 operations also include a publishing house, Internet provider and cultural centre. As an independent media under Milosevic, B92 and its boss experienced many inconveniences; Matic’s life was even in danger in 1999, when there was a plan to murder him after the assassination of Dnevni Telegraf (Daily Telegraph) publisher Slavko Curuvija. At that time B92 was banned, and Matic was arrested and detained for a short period. After Milosevic left politics, Matic and other leading people within B92 managed to maintain an independent editorial policy by not allowing the entrance of dirty capital into the ownership structure; recapitalization was done through investment funds, while a significant part of the shares were held by Trast B92, a company where B92 editors and managers have management rights, but cannot sell their stakes to anyone. Last week in Zagreb, Matic participated in the South East Europe Media Organization (SEEMO) conference, co-organized by the NCL Media Grupa. The topic at the SEEMO conference was “European standards and practice in Serbia” and there was a warning that the implementation of these standards were postponed due to fear that there would be a loss of the control mechanism over the media which was created in the former period, as well as the fact that the pluralism of solutions in European countries is being used in order to show everything as being a European standard. “At the 618th annual celebration of the Kosovo battle, I played around with the motives and facts that Milos Obilic is considered by Serbian media-mythological interpretation to be a Serbian, while Albanians call him Kobilic and refer to him as their own; when Serbia and Albania were in a alliance, he stabbed one of the then world leaders, the Sultan Murad IV and I asked whether this classified as a war criminal and if it would be necessary for my colleague the Albanian from Kosovo and I to apologize to Turkey for this crime, and, based on the current standards, should Obilic/Kobilic be put to trial“, said Matic.

NACIONAL: In Croatia, many know of B92 as a media house which opposed Milosevic. What type of a media house is B92 actually?

-B92 began its operations in 1989 as a small, local so-called youth radio which quickly turned into one of the pillars of opposition against not only Milosevic but all nationalistic and tyrant movements and ideas. From a city radio, which could not even be heard throughout the entire city of Belgrade, we have become a global media through which, today, we carry out operations such as television and radio, a website which, for many years, has been the most visited Internet media not only in Serbia but in the Balkans, a publishing house, music production, film production, cultural centre and bookstore. This diversity did not appear overnight. It was a way to fight and survive in Milosevic’s era. We had everything but the television station back in 1996.

NACIONAL: You were isolated from all other media in Serbia for years. What did that look like and what is the situation today?

- Our isolation was not only the consequence of the political and value system that we nurtured, but undoubtedly also the cultural and aesthetic values. We have not changed in that sense. In our programs, you still cannot hear turbo folk or see world celebrities in that sense. Our persistence, however, paid off: not only have we expanded our public but we have also made it desirable for other media to do the same. Everyone, however, today has to be careful not to offend our public. Very rarely do we hear accusations that our public is disloyal. But, even today, we often have a situation in which we are exposed to campaigns and pressure, mainly by the radical right wing forces gathered around the Serbian Radical party who identify B92 as a much greater threat to their existence than other political parties, because they perceive us to be a branch of extremism, primitivism and aggressive nationalism.

NACIONAL: The beginning of your personal media career was connected to Zagreb’s Radio 101?

- I began journalism in 1984 with the youth show ˝Rhythm of the heart˝ in Studio B. In 1985, I became a correspondent for Radio 101 and Radio Student from Ljubljana. Together we worked on the co-production of the ''Krezubi trozubac'' show, a provocative political weekly magazine which covered the political events in the then Yugoslavia. Disintegration was underway at that time, and each of us seized our piece of free speech, which ¨Krezubi¨ gathered in one spot in the Radio 101 studio. Franci Zavrl reported from Ljubljana, following editor Mladina, during the time of arrests and bans; in Zagreb, the team was composed of Davor Ivankovic, Ivo Skoric, and Hloverka Novak was the host of the show. It was very exciting, we were aware of the historical events, reinforcing Milosevic’s rule in Serbia. Then, the police began eavesdropping in on me because of my work, which I was convinced of after listing through my dossier given to me after the fall of Milosevic. Of course, the dossier was burglarized, and a clearly large number of documents were removed, but, based on various decisions by the Police Ministry, I was able to establish that there was more eavesdropping, but no transcripts. The start of my journalism career without censorship and self-censorship was a very good foundation for everything I have done since then. Of course, that experience helped me in the successful start-up of B92.

NACIONAL: You established Radio B92 in May 1989, two months after Milosevic absorbed the autonomous districts in Serbia with constitutional changes. Did you foresee how much your media career would be connected to him?

- When Milosevic came into power, we were aware of what that meant. I remember when one colleague from Radio 101 came to Belgrade; our mutual comments were full of concern due to the clear return to the past. However, I could not imagine that Milosevic would rule for more than several years. I believed that his rule would be short-term and that a much greater problem would be transforming the country into a prosperous democratic society than the appearance of nationalism. But the following year, it was already clear that this would not go by easily. Things began to pick up speed in every sense.

NACIONAL: What did the worst days under Milosevic’s rule look like?

- The worst was definitely when the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina began. It seemed that Milosevic was unstoppable. That is when most people left Serbia. The feeling of seclusion was horrible. And then the protests began, and with them our maturity. The peak was in 1996 when the magnificent civil protest began which lasted for over three months. They disabled our antenna and stopped our program for two days. That is when we first began to broadcast our radio program over the Internet, began to publish brochures, and we directly began to become politically active, and connect ourselves with the entire world. Even Milosevic had to give in. The following year, the Internet radio allowed connection at the national level for numerous local radio stations in Serbia. It all went up-down, hot-cold and broke people. The worst came during the bombings in 1999. I was arrested for a short time, the radio has been occupied by the regime, all journalists found themselves on the streets and I went to Montenegro for a short time. It was not easy at all, even though I was sure that this time Milosevic was not able to win and that, in the end, he would surely be defeated. However, the worst moments were those connected to the assassinations of our colleagues, the journalists and editors. Slavko Curuvija was killed during the bombings.

Upon completion of the bombings, I met up with a colleague on the streets, the chief editor of one daily newspaper, and he asked me whether my colleague informed me at the funeral of his message that I am next on the assassination list and that he had been informed of this by the Information Ministry. However, my colleague never told me this, which could have resulted in a tragic end because I was in Belgrade one month after the assassination of Curuvija. He told me that he did not have the strength to tell me that, so he told another colleague to tell me. He did not want to scare me, so he told one older friend who also assessed that it was better that I was not told. I had noticed that everyone was warning me that I should leave Serbia. Perhaps it is better that I did not know about this direct threat because I had to remain in Belgrade for a longer time and keep the team together, because everyone lost their jobs in those days and I had to organize solidarity actions to gather funds for all our other activities, and to secure that all fired from B92 would have something to live from. We succeeded in that, and several months later we established B2 92.

NACIONAL: How did you survive those times?

NACIONAL: How did you survive those times?

- Hot-cold, something like that. There was despair and pride, satisfaction and fulfilment. Quite often there was the feeling of unreality. As the chief and responsible editor, I survived everything which was occurring to the dissenters, democratic journalists, minorities, and peace activists. To maintain my mental health, we created a parallel world and created parallel institutions within it: we established the ''Cinema Rex'' cultural centre which exists and operates today, as well as editorial production, music production, and two magazines. The greatest concern was for my family. I have a daughter and son who grew up together with all the problems that both my wife and I faced. Their existence and security was something which always hovered over what I was doing. I think it is a huge success in such circumstances to maintain a marriage and family.

NACIONAL: At that time, you received a lot of assistance from outside. Who were your donors and do you still have donations today?

- We received various different types of assistance, from moral to solely material. And there was also mixed assistance, small organizations which gained funds alone to purchase, for example, batteries for walkmans, audiocassettes, and headphones. Some sent books, thinking that they could help us with that. Some confused us with Sarajevo, and sent us canned foods. Even today we are in touch with many divine people from the entire world who assisted us in different ways. Of course, there are no longer large donations. We now fight alone to ensure that our values find their way to people and the market. Without individual donors in our media, there would not be enough strength to develop. Serbia, at the end of Milosevic’s rule, had a very developed and connected media scene. I led the Association for Independent Electronic Media, ANEM, in which there were over 60 radio and TV stations which we connected via satellite programs. When B92 was banned for the final time, we created the largest media action in Europe since WWII, setting up transmitters throughout Serbia and broadcasting our program, although banned, from Belgrade via the Internet, and then via satellite to transmitters outside the country. One of the transmitters in Bosnia and Herzegovina was destroyed with a racket, but we set it up again and continued our broadcasting. The ANEM network practically was the backbone of the resistance movement and the peaceful march towards Belgrade which ended with the peaceful overthrow of Slobodan Milosevic’s rule. Our strategies are taught at numerous world media programs, and B92 is a sort of centre for the education of journalists who work in repressive conditions, from media in Eastern Europe, central Asia, and the Middle East to Zimbabwe. We know best how much solidarity meant to us when we needed it and now we do not refuse anyone who seeks assistance from us. We recently had colleagues from Iraq who wanted to create an independent radio station in Baghdad. After training with us, they returned to Baghdad with their initiative which, unfortunately, they did not manage to create for understandable reasons and all had to leave Iraq.

NACIONAL: How did you protect your journalistic and editorial integrity in difficult times?

NACIONAL: How did you protect your journalistic and editorial integrity in difficult times?

- This protection was more of a personal, psychological nature than actual or physical. Each of us was very aware of the risks and dangers of the profession. Oftentimes one word or look is more encouragement than security which, furthermore, we never even had. Strategically, we forced Milosevic’s regime quite early into a situation where, to stop us, he would have to physically liquidate us. We constructed a strong foothold in Serbia and a strong network of permanent solidarity around us. When we discovered the Internet in 1995 and tried its possibilities; in 1997, we were aware that we were indestructible. When you clear that issue up, then it’s only a question of the techniques and training of the journalists, who were very connected to home and what we were doing.

NACIONAL: Do you agree with the hypothesis that economic independence is the only guarantee of independent editorial policy?

- I know for certain that without economic independence there is no editorial policy, and later all else follows. We really tried during the period of donations to have economic independence from each individual donor, in such that we created a donators group who controlled each other, to maintain the basic principles that are promoted at B92. Today in Serbia, economic influence, the type that comes from advertisers, is stronger than political influence; because there are domains in which monopolies rule, this influence can severely threaten economic independence. However, through strong and competent marketing, attractive television programs such as the Champions League, Big Brother, highly viewed news and other programs, as well as excellent results such as 30% annual growth in television, we have been able to impose ourselves as an unavoidable media group for all advertisers; if someone wants to put pressure on us, we waiver the advertising. We already have this possibility calculated and we depreciate it with increased work with other advertisers. I hope that we will, through close cooperation and solid boycotts, block any tycoon who wants to influence the editorial policy of any form of media in this sense.

NACIONAL: What is today’s government and political situation in Serbia? Is Serbia finally moving towards Europe?

- I think we are moving towards Europe, but I do not know how long that path will take. I am afraid that there are many obstacles and ambushes, challenges, among which the future of Kosovo is the greatest test. It seems to me that the negotiations on Kosovo never existed, nor did the serious political process of solving the Kosovo crisis. There is a possibly successful way, as shown by Miroslav Lajcak, the Slovakian diplomat who led the referendum in Montenegro. I think for Kosovo needs a much wiser and comprehensive politician who knows the region instead of Ahtisaari, who came with an already defined conclusion. Apart from that, more time is clearly necessary. And of course, an open political debate is a priority. I was recently at a working lunch with one western diplomat who called upon our media responsibility and insisted that we do professional reports and tell the Serbs the truth that Kosovo is the precondition for Serbia’s European integration. He asked that the conversation be treated as ''off the record''. I then asked him what we were supposed to broadcast, that which they tell us ''off the record'' or that which they speak publicly, that Kosovo is not a prerequisite for European integration. This is really an irresponsible approach which gives birth to great confusion, and those with extreme opinions on all sides survive best in confusion which is the path that I am afraid of.

NACIONAL: Since the end of the 1990’s, you have found yourself under attack from several colleagues who claim that you are no longer with them on the same side. Concretely, these are accusations that you have opened your radio show to extremists and that you are working on forgetting war crimes?

- That simply is not true, although everyone has a right to judge someone’s public effect. We have always been open for dialogue and discussion on how to deal with the past in the best possible way. The topic of coping with the past was first brought up by us when Milosevic was still in power. Our programs still nurture this orientation even though, of course, this topic in no way is too commercial. Our thoughts were as follows: if we want to influence or change society, we have to be more viewed and popular. That is why we began with ''Big Brother'' and ''Who Wants to be a Millionaire''. Independence and influence comes with viewing. We did not, however, open up to extremists. Of course, unless they are criticizing us that our informational program covers the entire political and social scene. We, however, do not hide anything and we inform our viewers of everything. Even on skinheads and the emergence of fascism but with no attachment. Many people do not understand that media which emerged during times of great change are themselves condemned to change. Media which contributed to development, and want to continue participating in the development of society, imperatively need to develop themselves. B92 is that type of house, which changes its facade to maintain its spirit, risking its own spirit to strengthen it. It is very interesting that the largest attacks by extreme forces are against B92. Quite often posters emerge throughout the city attacking Jews and B92, there is a lot of graffiti with insults such as “B92 - Ustasha“; recently the Radical Party and the 1389 organization protested in front of our building. This all speaks clearly about our position and you do not need to review texts of this type because the facts speak the opposite.

NACIONAL: You have produced movies on war crimes, for example on Vukovar and Lovas?

- And that can be an answer to the previous question: in 1999, I started a project called “Nezavisni za istinu (Independents for truth)˝ which dealt with the production of documentary movies and series on our recent past. The movies investigate war crimes, from individual to mass crimes. Through the documentary movie “Otmica (Kidnapping)“ we unravelled the destiny of 16 Muslims from the village Sjeverin who were kidnapped in 1993 and their destinies were unknown to anyone until we investigated the case and uncovered the perpetrators – they took pictures of themselves as they tortured the kidnapped and we found those pictures. When we broadcasted the film, three were immediately arrested, and one later in Argentina: Milan Lukic who was extradited to the Hague. Therefore, the movie initiated the discovery and court proceedings, all were found guilty of large crimes, and the families of the kidnapped finally understood the sad fate of their dearest. That is the mission of this project. Soon a complete set of these movies and series will be published in DVD format for all libraries in Serbia, and we will attempt to make this complete set available to all libraries in the region. The movie ˝Lora˝ is also there, which we did in co-production with “Factum“ production, with Nenad Puhovski as an author; there will also be a movie on the crimes against Albanians in Suvoj Reci in Kosovo which we did in co-production with “Kohavision“. The series “Dobri ljudi u vremenima zla (Good people in times of evil)“ by Svjetlana Broz deals with the fates of those who put their lives in danger to save their neighbours of different nationalities, and so on. There is also a series on the influence of turbo folk on the creation of Milosevic’s cultural model. Of course, there are more than 30 hours of very educative and disturbing material. But what was said, if I remember correctly, by Zarko Puhovski: “reconciliation must follow anxiety“. Last year, we made a movie about the Vukovar tragedy with a combined team of journalists from Serbia and Croatia. The team was led by Drago Hedl, while direction was led by Janko Baljak. I am very proud of that movie because it was equally accepted after having premieres both in Zagreb and Belgrade, without serious objections. HRT is interested in broadcasting in Croatia and I think this will happen this fall. Over a million people have already seen this movie in Serbia. And here we go back to the concept of commercial strengthening. This movie, along with others, was seen by a large number of viewers thanks to its positioning following a very commercial and highly viewed timeslot. Therefore, with good programming, it is possible to protect and strengthen, as well as expand the basic values of the B92 brand, and through the commercial effect, we can maintain the possibility to deal with serious journalism research and a large regionally important project such as “Nezavisni za istinu“. We are just finishing up a documentary on the horrible crimes in Lovas, and have recently broadcasted a show on the same topic; we have re-editing it to include several actors who got in touch with us after the broadcasting. Drago Hedl and his team are now completing their work on that documentary.

NACIONAL: Your forums are one of the rare channels where Albanians and Serbs communicate over the last while; quite often there are discussions between Serbs and Croats, even though they are less serious?

- It will get easier when dealing with communication between Serbs and Croats via our forum. This is mainly because it is a similar social group of educated, younger, urban people. For them , accessing a forum is enough of a challenge to their wittiness, intelligence and tolerance. The relations between the two nations and people are more relaxed. The debates between the Albanians and Serbs are often dramatic, you can feel the issue of life or death, but I am glad that these debates are being led in a very constructive and tolerant fashion. Our informative program often profits from these debates and reports, because often we receive important and useful information before other media. Interaction is something which B92 has always believed in greatly.

NACIONAL: What is your life like when you are not working?

- I have the life of an average citizen. My daughter is already at university, my son has finished his first year of high school, and my wife is a technologist. We have another very important family member: our schnauzer Grej. I’m not obsessed with cars, I don’t even know how to drive. Books are important in my line of work where there is a permanent need for education. But I also relax best with a good book. Recently, I enjoyed the book “Snijeg (Snow)“ by Orhan Pamuk. I love books where I can both relax and learn something that I did not know before at the same time, which are especially important for my profession as well, such as Orhan’s modern Turkey and the disruption between modern and traditional in light of the expansion of the radical works of Islam.

NACIONAL: You do a lot of humanitarian work as well?

- Several years ago, in B92, we decided that there is not enough support of humanitarian actions and initiatives. Social needs are much larger than individual needs. We decided to approach these actions in an organized and thought-out way and that we will commit ourselves to the types of actions which can, in addition, motivate people and show them what we can do ourselves. The project of the construction of safe houses for woman subjected to domestic abuse initiated the whole society, especially the media, to make this problem visible and ensure that conviction and prevention becomes something normal. With that, we do more than care and assistance of the victims; we change the entire social climate. We are currently constructing three safe houses and our goal is to construct ten throughout Serbia. It is very different story with voluntary blood donations; this was something that was always desired, but which was not present enough. That is also the general problem of human solidarity which has the most sense when it is anonymous. Every summer, we have a situation where operations are postponed because we do not have enough blood in the banks. We felt that this is one of the greatest problems and tried to prove that this problem can be solved; we proved this in the first month of the campaign. We are now gathering funds for a large specialized vehicle to gather blood which will systematically alleviate this problem.

Latest news

-

28.10.2010. / 14:15

'A profitable INA is in everyone's interest'

-

28.10.2010. / 09:38

Sanader’s eight fear SDP — Won’t bring down Government

-

21.10.2010. / 15:02

Interior Ministry turned a blind eye on Pukanic assassination

-

20.10.2010. / 09:34

Barisic could bankrupt HDZ