Published in Nacional number 611, 2007-07-30

PARADOX IN THE FIGHT FOR HUMAN RIGHTS

CHC in an operation to free Zvonko Busic

The Croatian Helsinki Committee for Human Rights began actions to free the most notorious Croatian emigrant who, 31 years ago, after hijacking an airplane and killing a police officer, was sentenced to life in prison in the United States

The Croatian Helsinki Committee for Human Rights began actions to free the most notorious Croatian emigrant who, after hijacking an airplane and killing a police officer, has been serving time in an American prison for the past 31 years. This is the first time that the CHC has been reviewing an individual’s case who has been convicted of a terrorist act. Documents are currently being collected on the case, and it is expected that the US Justice Ministry will be sent a request for the release of Busic at the beginning of September, or at least a request that he be transferred to Croatia to serve the rest of his sentence.

The news about the unexpected operation was confirmed for Nacional on Friday 27 July by the President of the CHC, Daniel Ivin. Even though it was agreed that the details of this action would not be released to the public after a meeting held with his closest colleagues, Zarko Puhovski, Tin Gazivoda and Srdjan Dvornik, Ivin explained his motive in short: “Of course I do not support terrorism, especially a situation where a police officer was killed, but we believe that after 30 years of hard labour, Busic has done enough time and has the right to be set free. He has a legal right to freedom because it states in the verdict that, after serving thirty years, there exists a chance that he could be released. That is a ˝catch˝ in the judgement which goes in his favour. All I can say now is that we have taken over this case, and I am very optimistic that it will be solved”, said Ivin.

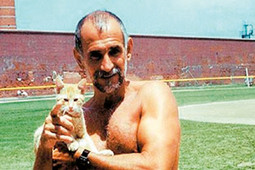

Zvonko Busic was born in 1946 in Gorica in Herzegovina; he completed high school in Imotski. As a 20 year old, he moved to Vienna where three years later, in 1969, he met American student, Julienne Eden Schultz. Busic studied Slavic Studies and History in Vienna, and Julienne Eden Schultz came to the capital city of Austria to perfect her knowledge of German. She quickly became involved in the work of Croatian political exiles, and after being persuaded by Busic, on Republic Day, 29 November 1970, she threw leaflets with anti-Yugoslav content from the high-rise on the Zagreb Republic Square with her friend Melody.

They were arrested and detained for one month in the prison in Djordjiceva, and returned to Vienna after their release. In 1972, Zvonko and Julienne Busic were married in Frankfurt; they then moved to Cleveland, United States, and later to Oregon. In the United States, they continued to move around emigrant circles, and Busic began to lobby for a large operation which would become world news.

Everything started to unfold in the fall of 1976 when Zvonko and Julienne Busic, Petar Matanic, Frane Pesut and Slobodan Vlasic hijacked American passenger flight TWA 35. The five hijackers entered the plane in New York’s La Guardia airport, and did not carry weapons with them; they had used material to make fake explosives, which they had wrapped around their bodies. Some time earlier, Busic had left a real bomb and propaganda material in a locker at the New York subway. When TWA 35 took off, he entered the pilot’s cabin and informed the cabin crew about the hijacking. Instead of its planned route to Chicago, the airplane was redirected towards France via Canada, where the final goal was Zagreb and Solin, where Busic’s team planned to drop leaflets promoting Croatia’s freedom.

Everything quickly went wrong, and police bomb technician Brian Murray died while dismantling the bomb in New York. After landing in Paris, the hijackers surrendered and were quickly transferred back to the United States. The consequences of the hijacking were catastrophic; world media portrayed the Croatians as terrorists, and Zvonko and Julienne Busic were sentenced to life in prison while Matanic, Pesut and Vlasic were sentenced to thirty years.

Everything quickly went wrong, and police bomb technician Brian Murray died while dismantling the bomb in New York. After landing in Paris, the hijackers surrendered and were quickly transferred back to the United States. The consequences of the hijacking were catastrophic; world media portrayed the Croatians as terrorists, and Zvonko and Julienne Busic were sentenced to life in prison while Matanic, Pesut and Vlasic were sentenced to thirty years.

If you can speak of mitigating circumstances, it would be the part of the verdict against Zvonko and Julienne Busic on the possibility of their conditional release. Julienne Busic used this and was granted amnesty in 1999. With HDZ in party the following year, she became the secretary for the Croatian Affairs office in San Francisco, and she moved to Zagreb and was employed in the Office of the President as Franjo Tudjman’s reliable colleague in 1995. She has had regular contacts with the CHC recently, who have been working on getting her husband released. The leader of the hijacking group, Zvonko Busic had much worse treatment than the others; he was sent to prison in the State of Georgia, and later transferred to the penitentiary in Otisville. In 1987, he managed to escape but was caught two days later and returned to prison. He served a certain period of time in Leavenworth in Kansas, which is on the list of the highest security penitentiaries in the United States. Last fall, the legal option for his release emerged because he had spent a full 30 years in detainment. Busic was serving in the Allenwood penitentiary in Pennsylvania and the media received information from the American Embassy that he had already been transferred to an extradition confinement where he was awaiting a final court decision on his release. In such cases, this is a routine procedure which lasts one month, during which time the American and Croatian administration must determine a method to transfer him to Zagreb.

Instead of that, an unexpected twist occurred: the courts decided that Zvonko Busic must return to detainment to finish serving his punishment. The law states that two years must pass before a new discussion emerges on an amnesty request which means that, if CHC succeeds, Busic would be freed in 2008 after 32 years of hard time. When it became clear that Croatian state institutions were incapable of procuring his release, the CHC became involved. Off the record, the members of CHC believe that they have a good rating in the United States of America, which increases Busic’s chances. During the 1990’s, there were many recorded cases in Croatia of human rights violations, evictions, job terminations, even assassinations of individuals with different political views and minority members. CHC opposed proceedings which were commonly supported by the then government, and they were especially prominent during the period following Operation Storm. At that time, their activists uncovered the terror that present in the liberated areas, where nearly 400 Serbians were killed and nearly 20,000 facilities were destroyed. Even though it was later uncovered that certain individuals who had been proclaimed dead has actually survived, the CHC reports are undoubtedly valuable documents from this period. Because of its operations, CHC had the support of foreign government, of which the most important was the US government.

Based on the relation of trust which has been established in the past, the current leadership at CHC is convinced that their request for the liberation of Zvonko Busic will result in a positive outcome. The attempts to free him or transfer him to a Croatian prison has lasted fifteen years, but objectively speaking, the chances for that were never large. When Tudjman’s regime attempted to procure Busic’s amnesty, the Croatian-Muslim conflict in BiH had already begun and the American did not want to consent to any form of compromise. Mate Granic, the former Foreign Affairs Minister testified that the return of Busic was Franjo Tudjman’s obsession. In mid 1993, after returning home from China, Tudjman asked his colleagues in the airplane how Busic could be assisted. Busic represented a symbol of resistance against Yugoslavia to him, as well as a bridge to radical nationalist groups from Herzegovina. When Granic travelled to New York and tried to initiate this question in a meeting with Madeleine Albright, then United States Ambassador to the United Nations, he was coldly refused.

Based on the relation of trust which has been established in the past, the current leadership at CHC is convinced that their request for the liberation of Zvonko Busic will result in a positive outcome. The attempts to free him or transfer him to a Croatian prison has lasted fifteen years, but objectively speaking, the chances for that were never large. When Tudjman’s regime attempted to procure Busic’s amnesty, the Croatian-Muslim conflict in BiH had already begun and the American did not want to consent to any form of compromise. Mate Granic, the former Foreign Affairs Minister testified that the return of Busic was Franjo Tudjman’s obsession. In mid 1993, after returning home from China, Tudjman asked his colleagues in the airplane how Busic could be assisted. Busic represented a symbol of resistance against Yugoslavia to him, as well as a bridge to radical nationalist groups from Herzegovina. When Granic travelled to New York and tried to initiate this question in a meeting with Madeleine Albright, then United States Ambassador to the United Nations, he was coldly refused.

Following the signing of the Washington Agreement in 1994, it appeared that the situation was changing, and when Tudjman met with Bill Clinton, he pleaded for Busic to be transferred to the Republic of Croatia. During the Dayton negotiations, Tudjman, Granic and Susak met with an American team led by diplomat Warren Christopher. Tudjman again sought Busic’s release, but received no answer. Later Miomir Zuzul attempted to lobby for his release but was unsuccessful. Granic believes that, at the end of the 1990’s, the initiative became unrealistic because America no longer supported Tudjman’s regime, and the attack on New York on 11 September 2001 was an unlucky circumstance against Busic’s chances for release. On that day, terrorism became the main enemy of the United States of America, and anyone who was convicted of a terrorist act could hardly count on receiving amnesty. The fact that Busic was returned to prison immediately prior to Ivo Sanader’s American tour last year is a coincidence. Right-wing media used that opportunity to attack Sanader because he never brought up the issue during his meeting with George W. Bush; they accused him of being an antagonist to Busic’s return to Croatia. The situation is, however, different and the hypothesis presented by the CHC that the current government institutions do not have influence on the American administration argumentatively works.

Following the signing of the Washington Agreement in 1994, it appeared that the situation was changing, and when Tudjman met with Bill Clinton, he pleaded for Busic to be transferred to the Republic of Croatia. During the Dayton negotiations, Tudjman, Granic and Susak met with an American team led by diplomat Warren Christopher. Tudjman again sought Busic’s release, but received no answer. Later Miomir Zuzul attempted to lobby for his release but was unsuccessful. Granic believes that, at the end of the 1990’s, the initiative became unrealistic because America no longer supported Tudjman’s regime, and the attack on New York on 11 September 2001 was an unlucky circumstance against Busic’s chances for release. On that day, terrorism became the main enemy of the United States of America, and anyone who was convicted of a terrorist act could hardly count on receiving amnesty. The fact that Busic was returned to prison immediately prior to Ivo Sanader’s American tour last year is a coincidence. Right-wing media used that opportunity to attack Sanader because he never brought up the issue during his meeting with George W. Bush; they accused him of being an antagonist to Busic’s return to Croatia. The situation is, however, different and the hypothesis presented by the CHC that the current government institutions do not have influence on the American administration argumentatively works.

Despite important political difference in relation to the Busic case, the Committee is convinced that the United States has violated his human rights with their refusal to free him after thirty years in prison. That is the basic motive, and most intriguing media interest for the Croatian Helsinki Committee for Human Rights since it has been established. If the CHC manages to free Zvonko Busic, it will be a result of the efforts of the institution which Croatian right-wing believers consider to be national traitors.

'USA violated Busic’s rights'

Zvonko Busic was sentenced to life in prison in 1976 in the United States as a leader of a terrorist group which hijacked a passenger airplane and placed a bomb in a New York subway. His wife was also then sentenced to life in prison, American Julienne Busic, whom he met in Vienna at the end of the 1960’s where he emigrated.

Zvonko and Julienne Busic, Petar Matanic, Frane Pesut and Slobodan Vlasic hijacked American flight TWA 35, which they boarded in New York’s La Guardia airport. They wrapped fake explosives around their bodies.

Busic left a real bomb in a locker in the New York subway. When TWA 35 took off, he entered the pilot’s cabin and informed the cabin crew about the hijacking. Instead of the planned route to Chicago, the airplane was redirected to France, where the final goal should have been Zagreb and Solin, where Busic’s team planned to distribute leaflets seeking a free Croatia.

While dismantling the bomb, a police bomb technician was killed and the hijackers surrendered after landing in Paris. Julienne Busic was freed in 1990. Busic received his right to amnesty last year but his request was denied. The Croatian Helsinki Committee for Human Rights is convinced that Busic’s human rights were violated after the United States of America refused his request.

Related articles

Banac and Cicak house HHO in the hovel

The Croatian Helsinki Committee (Hrvatski helsinski odbor, HHO), once a respected human rights organisation, faces its final fall. With the… Više

Latest news

-

28.10.2010. / 14:15

'A profitable INA is in everyone's interest'

-

28.10.2010. / 09:38

Sanader’s eight fear SDP — Won’t bring down Government

-

21.10.2010. / 15:02

Interior Ministry turned a blind eye on Pukanic assassination

-

20.10.2010. / 09:34

Barisic could bankrupt HDZ